Finding Meaning in the Meaningless

“Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.”

It is with these very words that Solomon—the wisest man to ever have lived, according to 1 Kings 3:12—opens up the Biblical book of Ecclesiastes, the book of poetry sandwiched in between Proverbs and Song of Songs, two other Biblical books which are primarily attributed to the famed teacher himself. Shortly after this dramatic opening statement, Solomon proceeds to discuss how “nothing is new under the sun” (1:9) and then moves onward, throughout the rest of the book, to discuss the meaningless of pretty much everything in life, including but not limited to wisdom, pleasures, folly, toil, advancement, and riches. “All of them are meaningless, a chasing after the wind” (1:14).

So what causes a man as wise as Solomon to believe such foolish things, and why on earth did such crazy declarations make it into the very text that defines our beliefs?

Or maybe the better question would be: Is he correct? Is everything really meaningless? Perhaps Solomon’s wisdom should be given the credit it deserves and we should prepare ourselves for the ultimate and slightly depressing revelation that everything really is meaningless. Perhaps there really is no meaning to be found on this earth. Perhaps this twelve-chapter long piece of dismal verse sheds some real light on the frailty and the reality of our universe and can provide us with a greater understanding of how we should treat the world itself given these dark insights. We, as Christians, believe that the Bible is true, so we can’t call the book false; all the same, we can’t just ignore the book and act like it doesn’t exist. If the Bible says, through Solomon, that “Everything is meaningless” and the Bible is God’s inspired Word to man, then you can bet your money on the fact that everything truly is meaningless, and you can also guarantee that there is something we can learn from that meaninglessness.

Depressing, I know, but perhaps there is light within the darkness. As we travel through the book of Ecclesiastes, we find ourselves crawling through a dark, gloomy, cramped tunnel where we can’t see anything beyond, so we just crawl blindly, etching further and further forward without knowing our destination. And sure, we could potentially be crawling into the deepest part of the cavern with no exit and only more darkness from which we will never emerge, but perhaps our crawling will lead us towards some unseen exit that will deposit us back into the light. Chapter-by-chapter we read each page, each word, and we find ourselves becoming more and more discouraged, our hearts growing heavy thanks to the discouraging words that seem to come forth from the teacher’s mouth. Is there really hope at all?

My answer, short and simple, would be yes, there is hope, but at the same time I would also 100% agree with the fact that yes, everything is meaningless. How can I make such a bold, seemingly contradictory claim, you ask? Well, the answer is much more simple than one would think, but before we look specifically at the context of the verses, we need to understand the context of the book as a whole, which will help us better understand how to interpret and read the book.

Ecclesiastes was most likely and quite understandably written in the latter days of King Solomon, in stark contrast two Song of Songs, which was probably written in the young days of the king, and Proverbs, which were probably written by the middle-aged man. But no, this book was written by a much older and wiser Solomon, having experienced the toils of life and seen the toils that it can have on the soul.

Having been raised in a royal household during the reign of his father David – a man after God’s own heart, as the Bible proclaims in 1 Samuel 13:14 and Acts 13:22 – Solomon grew up as a humble, God-fearing prince, so that whenever the death of his father came about around 970 B.C., his last words of wisdom to his son (1 Kings 2) would stick with Solomon throughout all of His early years, as he encouraged the people of Israel to praise and serve the Lord, just as his father David had done. Whenever God tells Solomon he will give him anything he wants, Solomon asks for wisdom, and as a result, God gives him not only wisdom, but fame, fortune, and everything that goes along with it. Solomon’s reign saw Israel flourishing and amounting to something unseen by such a small nation. From anyone looking at the nation of Israel at this time, it was obvious that some supernatural entity had a hand in their success. It was during these times of flourishing that Solomon pins Song of Songs and Proverbs.

But “what has been will be again, what has been done will be done again” (Ecc. 1:9), and if we have learned anything from the Bible up until the point we reach in Ecclesiastes, it’s that even great men stumble (look at Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, or pretty much anyone in the Old Testament). And for Solomon, what a great fall he takes. He begins to marry many, many women – 700 wives of royal birth, plus many more (1 Kings 11:3) – and before long, Solomon has abandoned the one, true God of Israel and has begun to worship the gods of these foreign women. What started as political alliances through marriage has sprouted into idolatry and folly. Solomon was given, by God, everything a man could ask for – money, power, wisdom, knowledge – yet even he falls away. He’s the most powerful man of his time, yet he falls away from the Lord who gave it all to him. “What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?” (Mark 8:36) And thus we arrive with the book of Ecclesiastes.

Reflecting on his life, the elderly Solomon puts his pen to the paper and, for one last time, begins to recite the wisdom imparted to him by God. “Meaningless! Meaningless!” he says. “Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless! What do people gain from all their labors at which they toil under the sun?” (Ecc. 1:2-3). Solomon, in his old age, has realized the foolishness of his ways: all the things before him are meaningless! The power, the money, the women—even the wisdom itself—is all meaningless. “I have seen all the things that are done under the sun,” he goes on to say. “All of them are meaningless, a chasing after the wind” (v.14). He has experienced all of the things the world has to offer, but he realizes that they are no good to him. They offer temporary satisfaction, yet no eternal reward. They have meaning at the time, but what good is a finite pleasure in terms of the infinite realm in which he—in which we—live in? There is none whatsoever; all of it is meaningless.

To sum things up, the word “meaningless” – better translated as vanity, to be worthless or futile – is used by Solomon 37 times over the course of the book’s very short twelve chapters. Solomon talks about the meaninglessness of everything under the sun, and even goes on to summarize his entire life in a mere two verses, highlighting the meaninglessness of it all:

“I denied myself nothing my eyes desired; I refused my heart no pleasure. My heart took delight in all my labor, and this was the reward for all my toil. Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done and what I had toiled to achieve, everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind; nothing was gained under the sun.” (2:10-11) Solomon knows what he’s done wrong. For the latter half of his life, he has lived a life of earthly pleasure by pursuing the ways of the world, seeking comfort in things like sex, drinking, and just having a good time (despite the very modern-sounding application, he alludes to these things throughout the book), and he realizes the problem with it all. He realizes the mess he has gotten himself into.

And this is all coming from a man wise well beyond his years. Solomon, on top of being a king, was an architect. On top of being an architect, he was a gardener. On top of these things, he was a philosopher, a musician, a botanist, a theologian, a zoologist, and a master entrepreneur – a polymath, the Leonardo da Vinci of his time. The fourth chapter of 1 Kings praises Solomon for the wisdom he displayed, yet here Solomon is, reflecting on his life, and he realizes that it is all for naught. He speaks of the natural progression of his life—constantly trying to pursue happiness—and how no matter what he did, he just couldn’t keep himself satisfied. Even the wisdom that God imparted on him did not please him, because over time, we can assume that he began to credit to himself rather than the one who gave it to him.

Then we reach what some would argue is the primary theme of the book, and whether you’ve been to a wedding, been to a funeral, listened to the Byrds, or watched Footloose, you’ve probably heard the passage before:

“There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens: a time to be born and a time to die, a time to plant and a time to uproot, a time to kill and a time to heal, a time to tear down and a time to build, a time to weep and a time to laugh, a time to mourn and a time to dance…” (continued, Ecc. 3:1-8)

This is the point where one might question Solomon’s motives: if everything is meaningless, then what are the importance of all these “times” he speaks of? Who cares about these special “times” set aside for all these earthly things? What does it matter?

I would argue that this is the first instance where the true meaning of the book comes into view: there is nothing wrong with earthly pursuits as long as they take place in their given time slot. God is in charge of the world and everything within it and beyond it, so His given “times” are undoubtedly the correct “times.” He gave us earth for a reason, so obviously there’s got to be some sort of meaning within it. Don’t mistake “meaningless” with “bad.” Pleasures aren’t bad. Wisdom isn’t bad. Toils aren’t bad. None of those things are bad. They just becoming fruitless whenever they are pursued outside of God’s appointed time. In other words, when earthly pursuits become your chief goal, everything truly is meaningless.

From here, Solomon goes back to his slightly depressing tone. He talks about the fallacy of richly pleasure: “Everyone comes from their mother’s womb, and as everyone comes, so they depart. They take nothing from their toil that they can carry in their hands” (5:15). Solomon, who would have known firsthand all the benefits of being rich, argues that even riches are meaningless – they will only serve you any good in this life, and if all those other things are meaningless, then those riches will be incapable of buying you anything of meaning. He goes on to further delve into these topics, comparing and contrasting wisdom and folly, and even discussing how whether you do good or bad things, we all share the same destiny: “As it is with the good, so with the sinful; as it is with those who take oaths, so with those who are afraid to take them” (9:2), and later, “For the living know that they will die, but the dead know nothing; they have no further reward, and even their name is forgotten” (v. 5). Depressing, I know.

Solomon continues to summarize his life, and the book just delves deeper and deeper into his soul – deeper and deeper into the metaphorical tunnel. At this point, it seems like there is no way out, and perhaps we have crawled to deep, so deep that we may never get out. There is no exit, and we will be stuck in this eternal darkness forever.

And then comes chapter twelve.

All of a sudden, there’s a huge tone shift in the book, and Solomon finally reveals the truth that he been hiding behind every single passage, every single word. For eleven chapters he has tricked us into believing that he was trying to make us lose our meaning in life, but at last he reveals that in reality, our eyes were closed! The exit to the tunnel was in front of us the entire time; we just failed to see it because we had failed to open our eyes.

“Remember the Creator in the days of your youth, before the days of trouble come and the years of approach when you will say, ‘I find no pleasure in them’—” (12:1)

Why should we remember our Creator? What does this have to do with the rest of book? Why is this just tacked on to the end of the book? These are all valid questions to ask.

And then, in a single instance, it all makes sense. You think about yourself crawling through that tunnel, and you remember the words that had been spoken to you from the very moment you entered: “What do people gain from all their labors at which they toil under the sun?...I have seen all things that are done under the sun; all of them are meaningless, a chasing after the wind” (1:3, 14). From the very first chapter, Solomon told you the answer to this seeming meaningless in life: Things are only meaningless when you approach them under the sun. Under the heavens. Under God, who gave it to you all. God gave Solomon the wisdom, and for the time when he attributed that wisdom to God, their nation flourished and he was happy with life; as he began to attribute it to himself, it lost its meaning, and he lost his happiness. God gave him the power, God gave him the riches, God gave him everything he would need…yet they were all meaningless when they were separated from God. The greatest gift, when separated from the giver, becomes a meaningless possession, but even the smallest of gifts, when associated with the one who gave it, can become the most prized possession in the world.

This is why Solomon commands us to remember our Creator in our youth. As a youth, he himself was raised by a man who was chasing after the heart of God, a man who all the kings of Israel who be compared to for the rest of time. He was raised in a godly household where he had no trouble forming a solid relationship with his Creator, but the moment that godly influence left his life, his own morality began a steady incline. So, as he looks back on his life, he’s basically telling us to not make the same mistakes that he did in life. The words of Kenny Rogers come to mind:

Promise me, son, not to do the things I’ve done

Walk away from trouble if you can

It won’t mean you’re weak if you turn the other cheek

I hope you’re old enough to understand

Solomon begs us to listen to him, to realize that even men of God will stumble in their ways. Temptation is ever present, and it is often in the times that we assume ourselves to be especially close to God that we find ourselves especially far from him. It happened with his father David when he killed Uriah the Hittite in order to claim the man’s wife as his own, and Solomon realizes that it has happened with him as well. He speaks to his children and he speaks to us, imploring us to find our true meaning in life, which can only be found in God. And, to put a modern spin on things, I would argue that in a sense, this book is prophetic, for it speaks a level of truth that even Solomon would not have recognized at the time.

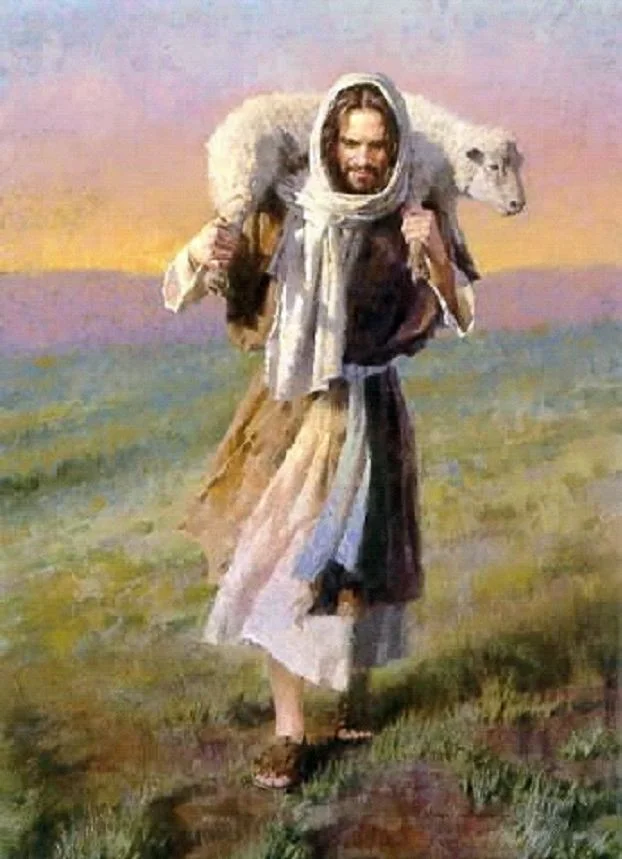

Instead of going on saying that everything is meaningless under the sun, I recommend we change it up a little bit: everything is meaningless under the Son. For God, in His love, decided to show us the true meaning of life by coming down to earth as a man—as flesh and blood—and while here, He showed us that pleasure isn’t found through the things of the earth. He wasn’t rich, He wasn’t married, He wasn’t given a throne to sit upon—all of those things are good, but not necessary. Instead, He came not to be served but to serve. The Lord of all creation, the one who sits at the right hand of the Father, came down to us and became one of us in the form of a man we now know as Jesus Christ, yet He didn’t place Himself above us, but rather below us. If you look to anything under the Son to find your meaning, you won’t find it. It’s in the Son that we find our true meaning. If you give Him the credit that He deserves, you will never lose your meaning in life.

“Now all has been heard; here is the conclusion of the matter: Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the duty of all mankind. For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil” (12:13-14).

It is with these final words that Solomon concludes his poem, and with those words he leaves some great theological advice: Don’t live by the ways of the world, for one day you will have to stand before the Father and answer for all you’ve done. It’s better to stand with God and be judged by the world than to stand with the world and be judged by God. Yes, we know that salvation is earned by faith in Christ alone (Ephesians 2:8-9), but one can earn their salvation while still living a meaningless life here on earth. Instead, we are called to be Christ’s workmanship (Eph. 2:10), and we are called to live lives of meaning, going out and sharing the Good News with all we see (Matthew 28:16-20). In this day and age, we see weekend warrior Christians who repent of their sins one day only to go and party the next with no intent of stopping, and while their salvation might very well be justified if their faith in Jesus is true, that’s not the life we are called to live. We are called to be brothers and sisters in Christ, and don’t brothers and sisters live within the same home? Our home here on earth is but a temporary lodging, like a hotel; instead, we should keep our focus on the eternal, and it should be our goal to go out and, as brothers and sisters, help those who are lost and have gone astray find their true home through Jesus Christ. That is where we find meaning.

That is what Solomon reminds us to do, for he realizes that despite all the good he did in the world, none of it would pass on to the eternal; it would all die with him. His 700+ wives, his riches, his studies, all of these things would pass with him, and what was the use of that? Remember your Creator, he reminds us. With all things we do, we should look to God. Give Him the glory, not ourselves. Give Him the praises, not ourselves. If we truly believe in Him, then should we not go on to obey His Word and strive to obey His commands? This is our calling, and this is the message of Ecclesiastes. You can find meaning in the meaningless, all you need to do is open your eyes.

So yes, everything is meaningless. Vanity.

Under the sun.

Under the Son.

But once you look to the Son and see the light He gives off, once you stand for a moment and just soak in His rays and feel the warmth and comfort pouring down upon you, that is when you will find your true meaning. You will find happiness in the Lord, not in the world. For everything there is a “time,” but God is above all things, and as a result, the time for God is eternally present, ongoing and never-ending. Once you recognize this, you will find comfort, satisfaction, and happiness within your life here on earth. That single moment of understanding is when you will be able to enjoy the earthly pleasures, but not put your meaning into them. So look to your Creator, my friends. If you look to Him, the world will sprout with a whole new sense of meaning.